Since I’ve been on a bit of a Chinese kick lately, I figured I’d continue the trend and share this post from my journal when I was living in China. I did a series of these, and I think they still hold up pretty well.

“China: Crapping on the world since 1949”

“Want to crush the human spirit? China has what you need!”

“My other car is a coal factory.”

“Feel free to leave your suggestions in the censorship box.”

These, and others, are some of the possible slogans I’ve been considering submitting to the Chinese government as endorsements for their great country. I think I’ve got the idea, but the wording doesn’t quite seem severe enough. I’ll keep working.

I just returned from a weeklong trip in Lijiang, a smallish city in the heart of Yunnan in southern China. It buts up against Myanmar (or Burma, for you imperialists out there), and is I suppose about as natural as China gets these days. It’s situated in the middle of a mountain range that I think eventually becomes the Himalayas, and has no shortage of Tibetan monks and monasteries. Although, I think the latter has more to do with the benevolent Chinese tourist trade than true cultural prosperity.

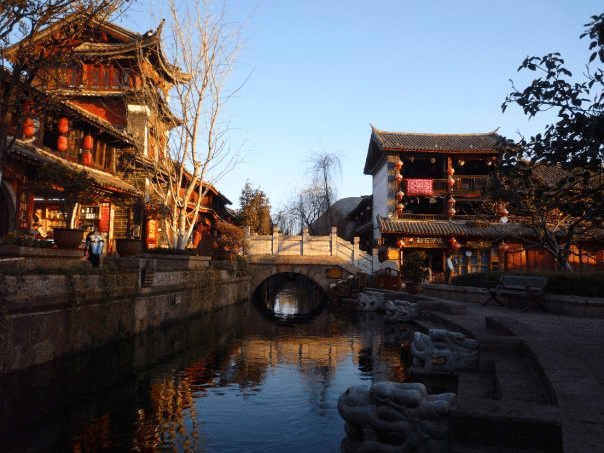

However, as much as it is a part of China, and therefore yet another nexus in the great web of human despair, it was a haven compared to the rural wasteland of coal factories and hicks that we left behind in Henan. There is a part of the city called “Old Town”—an ironic moniker considering that they’re still building it—but which is intended to represent traditional Chinese life. The buildings all appear very old, but that’s no feat in China. A brand new building, given a year or two, will match the dated look and feel of any crumbling building from the 1930s in America, complete with wandering, ruinous cracks and mouldering edifices.

The Old Town is built around a series of charming canals, with strikingly clear water and numerous koi and species of goldfish. It gives the very great impression of a Chinese Venice. Except without the history, legitimacy, or authenticity. But we were very appreciative, as it is very much a tourist town, and as such is chalk full of western food shops. I think I had pizza every night but one. To clarify for those who don’t know, pizza, along with cheese and clean air, is something of a mythological commodity in China. We were sorely grateful for the chance to indulge our shameless western fancies.

The first night we stayed in what we believed to be the bargain hotel of a lifetime. It was a charmingly quaint bed and breakfast, with elaborate furnishings and a delightful view into a tiny sunlit courtyard. I lamented that I had no female companion, because this was as ideally a romantic location as one could wish. And the price was an astonishing 60RMB a night. That translates to just over $8.00. That figure was magnified over the entire city, with ornate western meals costing around four or five dollars—roughly half as much as in Henan. I still don’t understand the exchange system, but as we ended up spending about 150RMB a day on entirely frivolous expenses, we didn’t really care.

And, even rarer than western food, there were westerners themselves! I saw on average about six westerners a day, and it was a sweet nepenthe to my aching soul. You cannot conceive the grandeur and majesty of the English tongue until you are berated with the clangor of chickens screeching in your ears for four months. And once I discovered the youth hostel, forget about it. There were so many English speakers I overloaded with joy. I even met a few German speakers, and had a chance to practice that ill-used skill which is, in China, less than useless. Since German is the only other language I speak, I have often found myself defaulting to that when I want to respond to someone in Chinese, which really doesn’t help anyone.

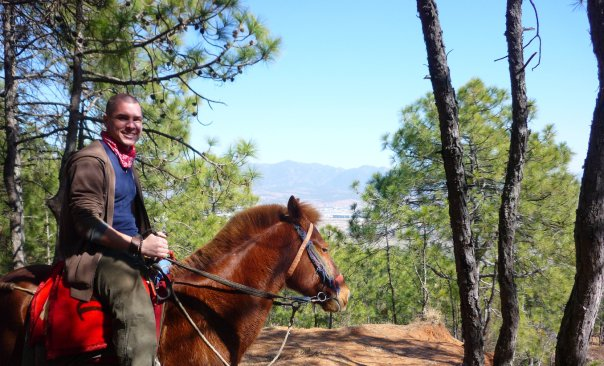

The second night there I met a Swiss woman who was staying with friends, and she, being an adventurous soul, decided to go with me the next day on a horse ride. I have been developing a latent passion towards equestrianism these past few years, and so when I saw a poster advertising a horse ride through the mountains, I knew I had to go. The pictures showed tourists galloping across a pristine wetland with a shimmering lake and imperious mountains in the background. And the price, $20 for a day, seemed right.

I met with Irene, the Swiss woman, early the next morning, and we set off to find the location. It wasn’t far, and as soon as we stepped off the bus, a horde of touts accosted us for offers on horse rides. They suggested the lofty price of $25 dollars, and we eventually talked them back down to $20. Bargaining in China mostly it’s just laughing at the price they suggest and then walking away. Actually haggling usually gets you nowhere, but the threat of a no-sale is great incentive for price reduction. So we headed off into the mountains astride our noble steeds, with an agreeably grouchy guide who left us to do whatever we wanted. I have ridden a few horses in my life, but I’ve never encountered such surly, ill-tempered, stubborn and lazy brutes as the little Tibetan mountain horses we were given.

No amount of prompting could coax my horse into anything more than an irritated trot, and spurring his sides with my heels more often encouraged him to go in reverse than increase speed. When I dismounted to take a picture in the woods, he waited patiently, but as soon as I got back on, a fairly normal procedure for most horses I presume, he bucked and took off through the forest as fast as he could. “Whoa!” means nothing to a Chinese horse, and tugging on the reins in every way I knew how succeeded only in making him rear or pull his head back with no effect whatsoever. When I tied him off and got down to pet him, he first tried to bite me, and when I backed away he tried to kick me.

I love horses—all animals, really—and so I resented this behavior. But in consideration of his life, and the care with which most Chinese treat their animals, I can really only pity him. We made our way to Baisha Lake, an inglorious little tarn which we were prompted to pay 30RMB ($4) to walk over to after we had dismounted. We laughed at this and walked over anyways without paying. There wasn’t much to see, so we rode back.

We took a route through the woods that carried us past an otherwise beautiful mountain vista, except that the industrious Chinese had decided that beauty was not an profitably exploitable commodity, and so had dynamited the hillside into ruin. Half the mountain was simply obliterated into rubble, which enormous trucks were carting away to be refined. What little natural beauty China has left, it is actively destroying. There is a quote that says, “If we are to love our country, our country must be beautiful.” I think the Chinese propaganda machine has simply bulldozed over that motto.

In a town north of Lijiang, I saw a poster advertising various places to visit in China and all the beauty the country had to offer. I was surprised to see a German castle on the Rhine as being a part of China. When your populace is too poor to travel, and the only news they get is from the government, why not tell them their country has an abundance of beautiful countryside, German castles, gorgeous, unpolluted lagoons, and hell—why not the Statue of Liberty?

And you’ll recall that we agreed on $20 as the price for the ride? Well, our hosts seemed to forget that fact, and demanded the outrageous sum of $25. Irene tried to argue with them, which was clearly going nowhere. I told her to give me her share, and together with my $20 I handed it to the woman. But she wouldn’t take it. I was tempted to just keep the money altogether, but I strapped the money to the horse and we left. My God, China. They don’t even try to treat you like you have a brain. Which stands to reason, I suppose. No one they’ve ever encountered has had one, so why should that change?

If yun nan wasn’t under communist control, I’d have moved there

LikeLike